In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, it became immediately clear to the worldwide scientific and research communities that a dire need was evolving to discover effective treatments for a rapidly increasing number of infected patients.

But before the St. Louis region had even seen its first case of COVID-19, WashU researchers were already brainstorming on how to best collect blood and other biological samples from infected patients so that the samples could be quickly disseminated to labs and researchers working towards treatment, prevention, and containment of the virus.

An Idea Put into Motion

At a meeting in early March 2020 led by William Powderly, MD, ICTS Director and WashU Professor of Medicine and Co-Director of the Division of Infectious Diseases, several WashU investigators gathered to formulate a plan of what quickly became a biorepository to streamline research efforts by storing and managing specimens collected from adult and pediatric patients who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Sample collections were led by Jane O’Halloran, MD, PhD, former WashU Assistant Professor of Medicine, and Philip Mudd, MD, PhD, WashU Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine.

“We had been collecting samples from influenza patients in the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Emergency Room for a few years prior to the pandemic onset, so we had a very good process in place to recruit subjects and collect samples from them,” says Mudd. “So, from this process, we had the plan for the biorepository drawn up, submitted to the IRB, and funded all within about 3 weeks. We collected the first patient samples within the first month. The timeline always amazes me when I think back to how quickly this all happened – it went from just an idea thrown out in a conference room to actually getting it done very quickly.”

The biorepository was rapidly launched with the help of funding from the ICTS, The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and the Siteman Cancer Center as well as input from the Community Advisory Board of WashU’s Institute for Public Health and the ICTS.

Christina Gurnett, MD, PhD, ICTS Associate Director and WashU Professor of Neurology, indicates that it made sense for the ICTS to oversee the biorepository operations because of its established involvement with numerous different investigators, departments, and core facilities. Gurnett says this is common of CTSA Hubs, to be able to quickly divert attention and lead the response to national health crises.

“The very definition of ‘translational science’ is the application of resources and tools to address problems important to public health,” says Gurnett. “At that time, we had been running this very large institute (ICTS) for 13 years at WashU. We knew the resources that could immediately be deployed to address the problems of the pandemic, including pilot funds that were redirected to support these critical projects.”

Gurnett also stresses that although the biorepository sprung quickly into action, much thought and careful decision-making went into its implementation. The purpose of the biorepository was to centralize the collection process, which propels research and prevents scientists from duplicating work already in progress.

“It sounded straightforward – we’ll just collect samples,” says Gurnett. “But we had to decide what kind of samples, and it wasn’t just blood – some individual labs wanted saliva or specific blood cells. We had to process and store them in ways that would be the most useful to investigators. And when we were collecting samples, we also had to consider the participants, and what state they were in as they donated their samples. By centralizing the process, we also ensured that investigators weren’t asking the same patient to be involved in dozens of research studies.”

All Hands on Deck

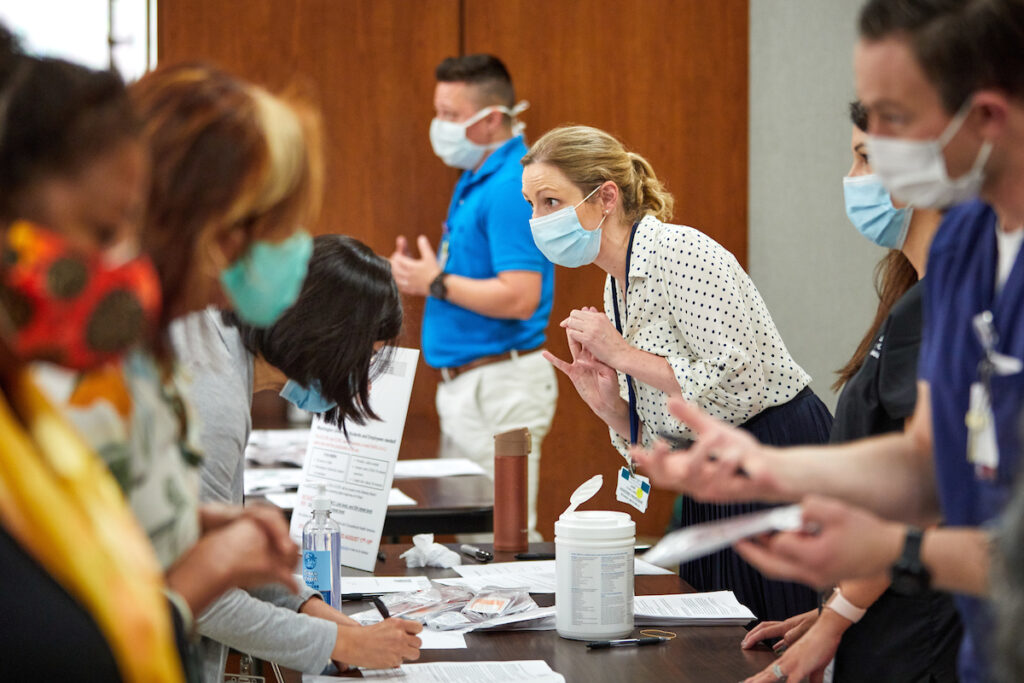

While the ICTS managed all requests for patient specimens from the biorepository, several different departments contributed to its overall success. Gurnett praises the collaboration and teamwork that took place, with dozens of faculty and staff members having a part to play on any given day, and specifically gives a lot of credit for the seamlessness of the biorepository to the Tissue Procurement Core.

“The Tissue Procurement Core (TPC) was immediately all hands on deck,” says Gurnett. “They not only provided the space in which to process, store, and distribute the samples, but they also allowed research technicians from other laboratories to come into the TPC and help process all the samples that were coming in. It took effort and volunteered time from many labs, even labs that weren’t even necessarily using the samples but were just volunteering to come in and help.”

Mark Watson, MD, PhD, WashU Professor of Pathology and Immunology and Director of the Tissue Procurement Core, attributes much of the far-reaching impact of the biorepository to the working relationship between the TPC, the ICTS, and the Siteman Cancer Center.

“ICTS investigators were able to work with Siteman Cancer Center leaders and rapidly leverage the existing infrastructure of the TPC to develop protocols and resources to support a COVID biorepository,” says Watson. “This unprecedented, collaborative effort resulted in several seminal publications that contributed to the broader understanding of viral pathogenesis and led to novel approaches aimed at detecting, treating, and preventing COVID-19 in patients.”

Mudd and Gurnett both also praise the contributions of the Emergency Care Research Core and the Center for Clinical Studies to the biorepository.

Input from Community Advisory Board

While collecting these biospecimens from infected patients, WashU researchers had to take into consideration that many of these patients would not be consented face-to-face due to exposure risk. Gurnett says that because the WashU IRB is so forward-thinking and there were already several studies in place using electronic consent, we were able to deploy these technologies quickly and ethically.

“We moved forward in so many ways during the pandemic in how we think about consenting and returning results to participants,” says Gurnett. “We used valuable input from the ICTS Community Advisory Board to think about the ethics of collecting samples, particularly for research where findings indicated underlying health issues, had implications for family members, or for participants who might have been quite ill at the time they donated to the biorepository.”

Hilary Broughton, MSW, Assistant Director of the WashU Center for Community Health Partnership & Research, says the Community Advisory Board (CAB) was quickly mobilized in May 2020 in response to the formation of this COVID-19 biorepository, and the potential for whole genome sequencing on these specimens. The whole genome sequencing would have the potential to reveal genetic mutations that indicated high-risk of developing a disease. The goal was for investigators conducting the COVID-19 research to be able to, with patient permission, return this important information and allow patients and family members to make informed decisions about their health.

“The CAB provided rich, individualized feedback from diverse perspectives on the topic of handling findings from these samples,” says Broughton. “The board’s comments were instrumental in how the consent process for the biorepository was approached. This is a great example of how guidance and diverse perspectives of community members enhance the local relevance, appropriateness, and value of clinical and translational research.”

Public Health & Research Impact

The specimens housed in the COVID-19 biorepository have proven to be an essential resource in research studies designed to develop new diagnostic tests and treatments, study biomarkers of disease severity, and for genetic studies to identify risk factors for severe disease. According to the Tissue Procurement Core, over 52,000 individual biospecimens from more than 700 COVID-19 patients were collected, and almost 23,000 of these specimens were rapidly distributed to 33 different WU investigators and their collaborators. Over 30 publications to date cite use of the biorepository.

Ali Ellebedy, PhD, WashU Professor of Pathology & Immunology, says studying and understanding the immune response the virus is inducing in people who have these infections has been the first step in developing the best treatments, and the availability of the specimens in the biorepository has been absolutely critical to those efforts.

“In general, for many investigators at WashU, they did not previously have access to human samples or were not used to working with human samples,” says Ellebedy. “This biorepository gave them that outlet and the opportunity to answer many important, wide-ranging questions,”

ktsdesign / Shutterstock

Ellebedy’s own use of the biorepository samples led to highly impactful research projects that were featured in an NIH Research Matters profile and two different New York Times articles – one highlighting persisting immunity to the virus and another discussing immune reaction set off by vaccines. Rachel Presti, MD, PhD, WashU Professor of Infectious Diseases, also led these ground-breaking studies using the biorepository that suggested even mild cases of COVID-19 leave those infected with lasting antibody protection, and that immune response to vaccines that utilize mRNA technology is both strong and long-lasting.

Mudd believes that the existence of the biorepository and the collection of its samples also added a glimmer of hope of combating the pandemic, especially to those who were patients themselves or family members of patients.

“Overall, patients were enthusiastic about giving their samples and participating in this research,” says Mudd. “And for family members, not only seeing how serious this was for their loved one but also seeing on the news how it was affecting so many others as well, this provided a way that they could help others and forward the research to discover better treatments for this disease.”

Mudd and Ellebedy worked together on a study using samples from the biorepository that found less inflammation in COVID-19 patients compared to those with influenza, which wasn’t originally thought to be the case. Mudd says this early discovery about the lack of severe inflammation helped other investigators design more effective treatments for the disease.

“The disease’s effects on older adults vs. younger adults, its effects on the lungs, how different treatments and drugs manipulate the body’s response… there have been so many examples of really great use for these samples. It has been an incredible and innovative resource for the community at large.”

Ellebedy

With the use of these samples having diminished substantially over the past two years, the COVID-19 specimen biorepository at WashU ceased operations in May of 2024. Further questions about the contributions of the biorepository can be directed to icts@wustl.edu.