Rare diseases are just what their name implies – each one affects a limited number of people. But with this rarity comes unique challenges, and among the biggest challenges faced by these patients are the roadblocks they encounter with gathering information about their conditions, being properly diagnosed, and finding the best resources and treatment options available.

One of these rare diseases is Wolfram Syndrome (WS) – a fatal genetic disorder characterized by juvenile-onset diabetes, vision loss, deafness, breathing difficulties, impairments in gait and balance, and neurodegeneration. Signs of WS start appearing in children as young as 6 years old, and it is often fatal by mid-adulthood because of its impact on multiple organs. Currently, there is no cure for WS, and treatment strategies focus on life-sustaining medications, clinical monitoring, and management of symptoms. Fumihiko Urano, MD, PhD, WashU Professor of Medicine, Pathology, and Immunology and Director of the Wolfram Syndrome International Registry & Clinical Study, is a driving force worldwide in the basic science, clinical, translational, and interventional studies of Wolfram syndrome and related disorders.

Urano says that, as of right now, if a patient is confirmed to have WS, it is incredibly overwhelming for them, and parents often make the difficult choice to delay informing their young children of this new reality, as all it takes is a simple internet search to convey the bleakness of the prognosis.

“Most of our patients are very smart and have normal cognitive functions, which means they know exactly what’s going on with their body and are fully aware that their functions are declining year by year,” says Urano. “That is tough, because they know they will eventually lose their eyesight, their ability to move around freely, and eventually, their ability to swallow and breathe. It is a truly terrible disease.”

Efforts for Treatment & Discovering a Cure

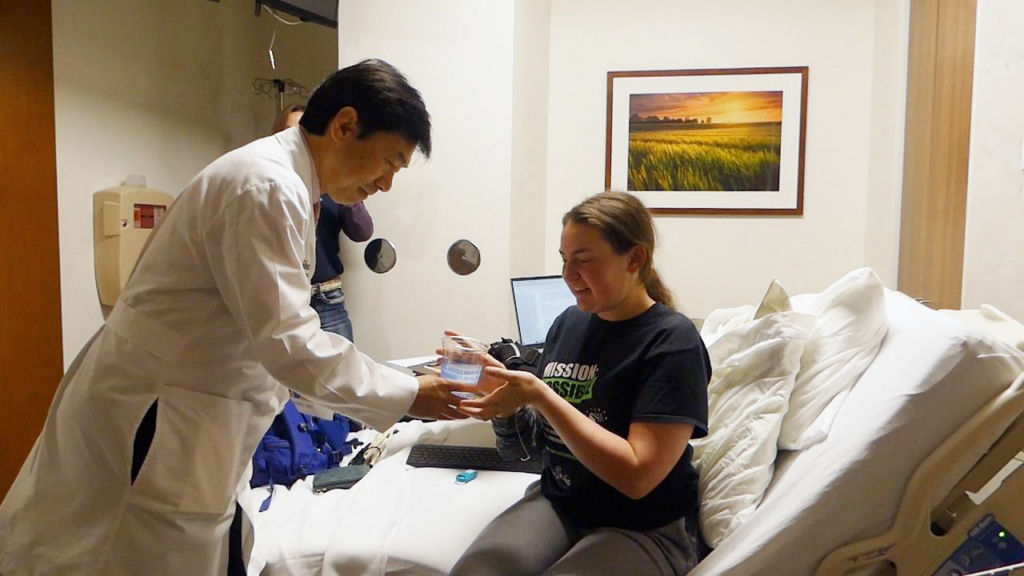

In 2011, with support from an ICTS Pilot Funding Award, Urano launched what is now known as the Wolfram Syndrome and Related Disorders Clinic. The clinic offers evaluation for suspected WS cases, education about WS, and counseling for those affected by WS. A variety of specialists can meet with patients, including neurologists, neuro-ophthalmologists, and urologists. Urano points out that with WS being such a rare disorder, it is important for patients to have a place where they will receive a top-quality, personalized care management plan.

“At our clinic, we gladly accept in-state patients as well as out-of-state and international patients,” says Urano. “WS is such a rare disease and there are not many specialists for it, so we really aim to provide the best clinical services available for these patients.”

Urano has also played a crucial role in establishing the WashU International Registry & Clinical Study for Wolfram Syndrome, which is aimed at gathering information about the disease’s natural history and biological specimens from patients with WS. This registry and associated natural history studies have provided valuable insights into the genetic information and natural course of the disease, and its associated comorbidities. Urano says understanding the progression of the disease is vitally important, because if predictions can be made about how a patient’s functions may deteriorate, some of those things can be acted upon in advance, improving the patient’s overall prognosis.

“Since we know that a patient with WS is likely going to develop swallowing problems, we can check their swallowing abilities early,” says Urano. “If issues are arising, we can refer them to a speech pathologist who can help them deal with these issues and slow their development. We also know they will lose their balance gradually, so we can refer them to physical therapy and occupational therapy if we begin to see this happen.”

Urano believes finding a cure for WS lies in the 3-step formula. The first step is to delay the progression of the disease using oral medications. The next two steps of stopping the progression of the disease are by using gene-editing therapies and replacing damaged tissues in patients using regenerative therapies.

“In theory, because all WS patients have mutations in the WFS1 gene, this is the root cause of the disease,” says Urano. “So, by correcting that mutation with gene-editing, we should be able to stop the progression. And by using regenerative therapies, for WS patients who have lost insulin-producing cells or retinal ganglion cells, for example, we can better manage their diabetes and vision problems. We have done a lot of work for several years studying potential drug therapies for WS, but now we are also moving more into studying these other kinds of therapies.”

Finding Success with ICTS Support

For over a decade, the ICTS has been supporting Urano in his WS research and has documented Translational Science Benefits Model (TSBM) case studies on his work. Urano expresses that he likely would not have been able to make the progress he has without this support. Two of the many ICTS services he has used over the years that he praises are the Clinical and Translational Research Unit (CTRU) and the Pediatric Clinical Research Unit (PCRU).

“In clinical trials, we typically run multiple tests on each patient, so this is very extensive work,” says Urano. “I do have a nurse coordinator on my team, but it is almost impossible for one person alone to be able to handle these types of trials. The CTRU and PCRU have many experienced nurses who have been involved in several clinical trials and who have been very helpful to my research team.”

Urano also expresses his gratitude for the ICTS funding he has received over the years. With support from a 2015 STAR Award, a 2016 JIT Award, and while using application preparation services in the Regulatory Support Center, he secured FDA approval for a clinical trial involving Dantrolene sodium, a drug used to treat muscle spasticity. The first patients were enrolled in the Dantrolene Clinical Trial in February 2017, and the team was able to identify the drug as a potential therapeutic target for WS, especially in treating its critical component of molecular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) dysfunction.

Urano also points out that several years ago, with help from the ICTS, he was able to facilitate a personal connection with the leadership team at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

“The ICTS was very helpful to me in starting collaborations with leadership at NCATS to study drug therapies for WS,” says Urano. “I have been able to meet with many scientists at NCATS who have become interested in WS, and in a current clinical trial we are working on, NCATS ended up assisting us with some experiments and submitting data to the FDA to begin the trial. They have been very helpful and are very generous!”

Ongoing Work & Next Steps

Building upon his previous research on ER dysfunction, Urano is currently working with Amylyx Pharmaceuticals on a Phase II clinical trial designed to study the safety and tolerability of the investigational drug AMX0035 in participants with WS. It also aims to determine if AMX0035 may slow the worsening of clinical signs and symptoms of the disease. Interim data was shared in a webinar on April 10, 2024. Data indicates the trial has so far demonstrated improvement in several functions, such as vision and glycemic control, and the medication has been generally well-tolerated by all participants. Finalized data is expected by the end of this year, and the research team plans to engage with regulatory authorities to further the drug’s potential development.

Urano says he also plans to continue working closely with patient organizations, such as The Snow Foundation and The Ellie White Foundation, in efforts to maintain the public interest in finding a cure for rare diseases, like WS. He says it is important to keep these patients and what they go through at the forefront of our minds.

“Our patients are truly grateful for any news articles, publications, or any attention that is given to them and their rare disorders,” says Urano. “They appreciate knowing that people care and want to know more. It gives them hope.”

Fumihiko Urano, MD, PhD